Manual of Air Traffic Services (MATS)

Introduction

Definitions and abbreviations

ADS-B. Automatic dependent surveillance – broadcast. A means by which aircraft can automatically transmit and/or receive data such as identification, position and additional data, as appropriate, in a broadcast mode via datalink.

Air traffic flow management (ATFM). A service established with the objective of contributing to a safe, orderly and expeditious flow of air traffic by ensuring that ATC capacity is utilized to the maximum extent possible, and that the traffic volume is compatible with the capacities declared by the appropriate ATS authority.

ATIS. Automatic terminal information service, the automatic provision of current, routine information to arriving and departing aircraft.

Ceiling. The height above the ground or water of the base of the lowest layer of cloud below 20, feet covering more than half the sky.

Dependent parallel approaches. Simultaneous approaches to parallel or near-parallel instrument runways where radar separation minima between aircraft of adjacent extended runway centerlines are prescribed.

Global navigation satellite system (GNSS). A worldwide position and time determination system that includes one or more satellite constellations, aircraft receivers and system integrity monitoring, augmented as necessary to support the required navigation performance for the intended operation.

Independent parallel approaches. Simultaneous approaches to parallel or near-parallel instrument runways where radar separation minima between aircraft of adjacent extended runway centerlines are not prescribed.

Independent parallel departures. Simultaneous departures from parallel or near-parallel runways.

Maneuvering area. The part of an aerodrome used for take-off, landing, and taxiing of aircraft excluding aprons.

Multilateration (MLAT) system. A group of equipment configured to provide position derived from secondary surveillance radar (SSR) transponder reply signals primarily using time difference of arrival techniques. Additional information, including identification, can be extracted from the signals.

Near-parallel runways. Non-intersecting runways whose extended centerlines have an angle of convergence or divergence of 15 degrees or less.

Standard instrument arrival (STAR). A designated instrument flight rule (IFR) arrival route linking a significant point, normally on an ATS route, to a point from which a published instrument approach procedure can be commenced.

Standard instrument departure (SID). A designated instrument flight rule (IFR) departure route linking the aerodrome, or a specific runway on the aerodrome with a significant point, normally on a designated ATS route, at which the enroute phase of flight commences.

Role of air traffic services

Air traffic services (ATS) primarily exist to expedite and maintain a safe and orderly flow of traffic. ATS ensures that collisions are prevented between aircraft, and between aircraft and other objects on the aerodrome surface.

ATS comprises of several services including flight information service, alerting service (for search and rescue), air traffic advisory service, and air traffic control service. Air traffic control service includes area control service, controlling larger sectors of airspace when aircraft are enroute, approach control service which is responsible for separating and sequencing aircraft in the terminal area, and aerodrome control service which manages aircraft on or in the vicinity of an aerodrome.

General Provisions

Altimeter setting procedures

Altimetry

Aircraft maintain their level primarily with reference to a calibrated barometer, known as an altimeter, that is set to a specified pressure setting. As atmospheric pressure decreases with altitude, measuring the pressure outside the hull of an aircraft can provide a means to measure its altitude.

Altimeters are calibrated to the ISA standard atmosphere and will indicate an increase in altitude of approximately 30 ft for every 1 hPa reduction in atmospheric pressure near sea level. Barometric altimeters only measure the altitude above the reference pressure setting and have no means of indicating an aircraft’s true altitude, so some adjustment is required for different atmospheric conditions to ensure that the indicated level is accurate.

Air traffic controllers must pass the required pressure setting information to an aircraft, based on its location and level above ground. This is important as aircraft with different or inappropriate altimeter settings will be flying at different true altitudes and may result in a loss of separation with other aircraft or with terrain.

Altitude

When aircraft are being flown with reference to a local pressure setting, or QNH, the level is expressed as an altitude in thousands of feet above mean sea level. QNH corrects for local pressure deviations and provides aircraft with an indication of their height above mean sea level.

For example, the level of an aircraft that is at an indicated altitude of 8000 ft with reference to QNH, would be expressed as an altitude of 8000 ft.

Altitudes are typically flown at lower levels, usually within the aerodrome terminal area where terrain separation becomes a factor. Altitudes can be quickly measured against known elevation of the surrounding terrain, which is important during the approach and landing phase.

Flight level

When aircraft are being flown with reference to the standard barometric pressure setting, the level is expressed as a Flight Level (FL), in multiples of 100 ft.

For example, the level of an aircraft at an indicated altitude of 36000 ft with reference to standard barometric pressure, it would be said to be cruising at Flight Level 360 (FL 360).

Typically, aircraft are flown at flight levels during cruise. This is done to avoid several altimeter setting changes as aircraft travel long distances where atmospheric conditions are different. During cruise, terrain separation is rarely a factor, and separation between aircraft is more important.

Ensuring all enroute aircraft are following the same altimeter setting simplifies the controller’s task of separating as aircraft as two aircraft at the same place will always have the same altimeter error.

Transition altitude and transition level

Due to the nature of aircraft altimeters, when transitioning from QNH to standard pressure, there will be an error in the reading, especially when atmospheric conditions are different from standard. This error may mean that aircraft following QNH may not be separated from aircraft following standard pressure at the adjacent higher level.

In order to avoid this problem, a transition altitude and transition level are established by each local ATS authority that ensure that minimum vertical separation will exist between aircraft referencing QNH and standard pressure.

The transition altitude is the highest available altitude to an aircraft with reference to QNH, whereas the transition level is the lowest available flight level (with reference to standard pressure).

The area between the transition altitude and transition level is known as the transition layer. Sustained flight within this layer must be avoided as adequate vertical separation may not be assured between aircraft.

Horizontal speed control

Airspeed

The airspeed of an aircraft is expressed in knots and, like barometric altitude, is subject to errors. Indicated airspeed is the uncorrected airspeed displayed to the flight crew and is an indication of “how much air” the aircraft is hitting at a given moment.

When a speed restriction is assigned to an aircraft for the purposes of separation, it will be with reference to indicated airspeed (IAS). Speed assignments must be applied in multiples of 10 knots.

True airspeed (TAS) is the true rate of movement of the aircraft through the airmass at a given time, corrected for instrument, pressure, compressibility and density error.

TAS rises by approximately two per cent for every 1000 ft an aircraft climbs when compared to IAS. For the purposes of ATC, however, to estimate an aircraft’s true airspeed, approximately 6 knots may be added to the aircraft’s reported indicated airspeed per every 1000 ft of altitude. Below 8000 ft, the difference between indicated and true airspeed is not significant and may be neglected.

In addition, controllers must also have an awareness of the current wind conditions, as a tailwind will result in an increased ground speed and a headwind will have the opposite effect.

Mach number

At higher altitudes, the effects of compressibility become the overriding factor in jet turbine aircraft aerodynamics. Because of this, Mach number is primary reference used to measure airspeed and any adjustments are applied in increments of 0.01 Mach.

For ATC speed control, Mach numbers are used above FL250.

Application of speed control

In order to facilitate orderly flow of traffic, ATC must provide aircraft with adequate notice of any speed control to be provided.

Speed instructions should be limited to those necessary to maintain adequate separation. Frequent alternating increases and decreases in speed should be avoided.

In order to maintain desired spacing, however, speed instructions should be issued to all aircraft concerned.

For aircraft entering or established in a holding pattern, speed control instructions must not be issued.

Descending and arriving aircraft

Arriving aircraft should, wherever possible, be permitted to absorb a period of terminal delay by cruising at a reduced speed before entry into a terminal hold. Instructions for aircraft to maintain “minimum clean speed” (the minimum speed of an aircraft with flaps and gear retracted) may be used for this purpose.

Other instructions to maintain “maximum speed” or “minimum speed” nay also be used to apply separation.

Speed reductions to less than 250 knots during the initial descent from cruising level of jet turbine aircraft should be avoided unless coordinated with pilots.

In addition, aircraft should not be instructed to maintain high rates of descent as well as to reduce speed simultaneously, as most aircraft will be unable to achieve this. Aircraft that are instructed to slow down during descent can be expected to maintain a short period of level or near-level flight to reduce speed.

Unless otherwise required by the terminal procedure or for traffic separation purposes, aircraft shall be permitted to operate in clean configuration for as long as possible below FL 150. The minimum clean speed for most jet turbine aircraft is approximately 220 knots. Speed reductions below this would require the use of flaps or slats.

Approach phase

During the intermediate and final approach phase, speed changes exceeding 20 knots must not be applied.

Controllers must be aware that aircraft must achieve a stabilized approach by 1000 ft above aerodrome level (AAL). As such speed control inside 4 nautical miles from touchdown should be avoided.

In addition, instructions to maintain speeds greater than 160 knots within an 8 nautical mile final should be avoided.

Vertical speed control

In order to maintain a safe and organized flow of traffic, aircraft can be instructed to adjust their climb and descent rates. This may be applied to two climbing aircraft or two descending aircraft to ensure adequate vertical separation exists.

Aircraft in a climb shall be issued a vertical speed greater than or equal to a specific value, or less than or equal to a specified value. The same method applies for aircraft in a descent.

In addition, aircraft can be instructed to expedite their rate of climb or descent through a specific level, or to reduce their rate of climb or descent.

Vertical speed control should only be assigned as necessary to ensure separation and frequent changes to climb/descent rates should be avoided.

When no longer needed, aircraft should be informed that vertical speed control has been cancelled.

Vertical speed control is expressed in “feet per minute” and in multiples of 100.

Separation Methods and Minima

Separation is required to ensure there is always a minimum distance between aircraft to minimize the risk of collision. This is provided by means of position reports, or by identification on radar.

There are two main types of separation employed by ATC: vertical and horizontal separation. If at any time one type of separation between aircraft is below the prescribed minimum, the other type of separation must exist. For example, if the horizontal separation between aircraft is below minimum, vertical separation must exist.

Vertical and horizontal separation must be provided:

- Between all flights in Class A and B airspace

- Between all IFR flights in Class C, D, and E airspace

- Between IFR and VFR flights in Class C airspace

- Between IFR and special VFR flights

When issuing clearances, the controller must ensure that it would not reduce the separation between aircraft to below the required minima. In addition, if one type of separation minima cannot be maintained, then another type of separation must be applied between aircraft before any separation minima is infringed.

Vertical separation

Vertical separation minima

Vertical separation is assured by assigning aircraft specific altitudes or flight levels in accordance with the altimeter setting procedures described in section 2.1.

Unless subject to the conditions described below, aircraft flying below FL 290 must be separated by a minimum of 1000 ft. Above this level, aircraft must be separated by at least 2000 ft vertically.

Reduced vertical separation minima (RVSM)

Special instrument and equipment installation is required for an aircraft to be able to operate in RVSM airspace. Between FL 290 and FL 410, RVSM may be applied. Most modern turbine aircraft are equipped to operate in RVSM airspace.

Under RVSM, for aircraft flying below FL 410, the minimum vertical separation is 1000 ft. Above this level, a separation minima of 2000 ft is applied.

Assignment of cruising levels

Aircraft will typically be assigned only one cruising level for an aircraft travelling beyond a controller’s control area. It is the responsibility of the next controller to issue further climb as appropriate.

ATC must also ensure that the cruising level is not below the published minimum enroute cruising level for a specified route or airway.

In general, aircraft already occupying a specified cruising level will have priority for that cruising level. For example, when two or more aircraft have requested the same cruising level, the preceding aircraft will normally have priority.

RVSM cruising levels

Cruising levels in RVSM airspace are assigned according to the semi-circular rule (Table 3-1). The semi-circular specifies cruising levels based on an aircraft’s planned magnetic track.

Additionally, any regional level restrictions must also be complied with in conjunction with the semi-circular rule.

Vertical separation during climb or descent

During a climb or descent, aircraft may only be permitted to initiate a climb or descent to a level previously occupied by another aircraft after the latter has reported vacating that level.

The only exceptions to this rule apply when aircraft are encountering severe turbulence, or their performance is markedly different, such as a lightly loaded 777 following an A320. For these cases, the second aircraft may only be cleared to the level of the fist after it has passed a level separated by the specified minimum.

Consideration must also be given to the vertical speed of aircraft descending in a holding pattern, to ensure that the separation minima is not infringed at any point. If required, ATC should specify minimum or maximum descent rates.

Horizontal separation

Lateral separation

Lateral separation is applied so that the spanwise distance between two aircraft never reduces to below a specified minimum. This is ensured by operating aircraft on different routes at different locations, by visual observation, by, the use of navigational aids or by area navigation (RNAV).

Lateral separation criteria and minima

Lateral separation can be applied through the following methods:

- By reference to position reports which positively indicate aircraft geographical location, visually or by reference to a navigational aid

- By reference to VOR, NDB, or GNSS on intersecting tracks or ATS routes separated by a minimum appropriate to the navigational aid used (Table 3-2)

| Angular difference between tracks measured at the common point (degrees) | 1000 ft to FL 190 Distance from common point | FL 200 to FL 600 Distance from common point |

|---|---|---|

| 15 to 135 | 15 NM | 23 NM |

| The distances given here are ground distances between aircraft | ||

Table 3-2: lateral separation between two aircraft flying VOR or GNSS on crossing tracks

Longitudinal separation

Longitudinal separation is applied so that the distance between two aircraft never reduces below a prescribed minimum on their longitudinal axis (nose to tail). Longitudinal separation will be applied for aircraft on the same or diverging tracks using speed control.

When applying time or distanced based longitudinal separation, controllers must exercise caution for aircraft with different speed characteristics. If a following aircraft maintains a higher speed than the preceding aircraft, speed control must be applied before aircraft are expected to reach minimum separation.

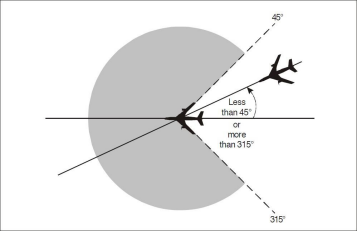

For separation purposes the terms “same track”, “reciprocal track”, and “crossing track” have the

following meanings (Figure 3-2, 3-3, and 3-4) :

Longitudinal separation minima based on distance using GNSS or DME

Aircraft maintaining separation with reference to any combination of DME or on board GNSS systems (RNAV) must be in direct contact with ATC though VHF radio.

The following minima applies for this type of separation.

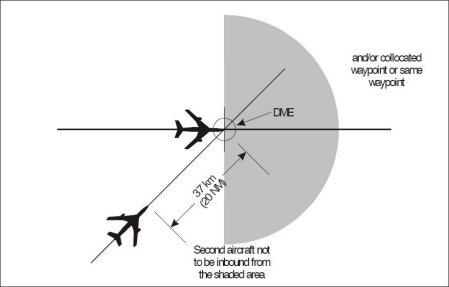

Aircraft at the same level

For aircraft at the same level, and following the same track (Figure 3-5) the longitudinal separation minima is 20 NM, provided each aircraft uses the following:

- The same “on track” DME

- An “on track” DME and a collocated waypoint where one aircraft is using DME and the other

- GNSS

- The same waypoint where both aircraft are using GNSS

Separation must be checked by obtaining constant GNSS based or DME based position data at frequent intervals. Aircraft that are ADS-B out capable will satisfy this requirement.

Reduced longitudinal separation

For aircraft at the same level following the same track, the longitudinal separation minima may be reduced to 10 NM, provided the leading aircraft is travelling 20 knots faster or more (Figure 3-6).

The same conditions as 3.2.4.1 will also apply in order to use this reduced separation.

Aircraft on crossing tracks

For aircraft on crossing tracks where the relative angle between the tracks is less than 90 degrees, the aircraft shall be separated by a minimum of 20 NM provided each aircraft reports a distance based on DME/collocated GNSS waypoint (Figure 3-7).

A reduced separation minimum of 10 NM may also be applied if the leading aircraft is travelling 20 knots or faster or more (Figure 3-8).

The same conditions as 4 .2.4.1 shall apply for both these cases.

Aircraft climbing or descending

The separation minima for aircraft climbing or descending through the level of another following the same track is 10 NM.

In this case, one aircraft must maintain the same level when vertical separation does not exist (Figure 3-9, 3-10).

The same conditions as 4 .2.4.1 also apply.

Separation in the Vicinity of Aerodromes

Procedures for departing aircraft

General

At aerodromes where standard instrument departures (SIDs) are established, departing aircraft should normally be cleared to follow an appropriate SID

If no specific procedures are established or aircraft are unable to comply with a SID, the direction of flight after take-off, the initially cleared level and any other necessary information should be passed to the aircraft.

Standard clearances for departing aircraft

Standard clearances for departing aircraft shall contain the following items:

- Aircraft identification;

- Clearance limit, normally the destination aerodrome;

- Designator of the assigned SID, if applicable;

- Cleared level;

- Allocated SSR code;

- Any other necessary instructions or information not contained in the SID description

Clearances on a SID

Where departing aircraft are expected to comply with all speed and altitude restrictions on the SID, the phrase “CLIMB VIA SID TO

When departing aircraft is cleared to proceed directly to a published waypoint on the SID, the speed and altitude restrictions associated with the bypassed waypoints are cancelled. All remaining speed and altitude restrictions remain applicable.

When a departing aircraft is vectored or cleared to a point that is not on the SID, all published speed and altitude restrictions on the SID are cancelled. If necessary, the controller shall:

- Reiterate the cleared level

- Provide speed and altitude restrictions as necessary

- Notify the pilot if is expected that the aircraft will be subsequently instructed to re-join the SID and the expected point where this will occur.

Procedures for arriving aircraft

General

At aerodromes where standard instrument arrivals (STARs) have been established, aircraft will normally be cleared to follow the appropriate STAR. The aircraft shall be advised of the type of approach and runway-in-use as early as possible. After coordination with the approach controller, the first aircraft may be cleared for the approach by the area control center controller.

An IFR flight shall not be cleared for an initial approach below the appropriate minimum altitude specified for the procedure unless.

- The pilot has reported passing an appropriate point as define by a navigation aid or as a waypoint; or

- The pilot reports the aerodrome is and can be maintained in sight; or

- The aircraft is conducting a visual approach; or

- The controller has determined the aircraft’s position by the use of an ATS surveillance system and a lower minimum altitude has been established for that sector.

Standard clearances for arriving aircraft

Where standard clearances are in use for arriving aircraft, provided no terminal delay is expected, the area control center may clear an aircraft to follow a STAR without prior coordination with the approach controller.

Provision shall always be made to inform the approach controller of the sequence of aircraft following the same STAR.

Standard clearances for arriving aircraft shall contain the following items:

- Aircraft identification;

- Designator of the assigned STAR if applicable;

- Runway-in-use except where part of the STAR description;

- Cleared level;

- Any other necessary instruction or information not contained in the STAR description

Clearances on a STAR

Where arriving aircraft are expected to comply with all published altitude and speed restrictions on a STAR, the phrase “DESCEND VIA STAR TO

When arriving aircraft are cleared to proceed directly to a published waypoint on the STAR, the speed and altitude restrictions associated with the bypassed waypoints are cancelled. All remaining speed and altitude restrictions remain applicable.

When arriving aircraft are vectored or cleared to a point that is not on the STAR, all published speed and altitude restrictions on the STAR are cancelled. If necessary, the controller shall:

- Reiterate the cleared level; and

- Provide speed and altitude restrictions as necessary; and

- Notify the pilot if is expected that the aircraft will be subsequently instructed to re-join the STAR and the expected point where this will occur.

Visual approach

An IFR aircraft may be cleared to execute a visual approach provided the pilot can maintain visual reference to the terrain and:

- The reported ceiling is at or above the level of the beginning of the relevant initial approach segment; and

- The pilot reports at the level of the beginning of the initial approach segment or at any time during the instrument approach procedure that with the prevailing meteorological conditions there is reasonable assurance that a visual approach and landing can be completed.

Subject to these conditions, clearance for an IFR aircraft to execute a visual approach may be requested by the pilot or initiated by the controller. In the latter case, the flight crew must agree to continue visually.

For successive visual approaches, separation shall be maintained between aircraft by the controller until the pilot of the second aircraft reports having the first aircraft in sight and is able to maintain own separation. Where both aircraft are HEAVY category aircraft or the preceding aircraft is of a heavier category, a caution of possible wake turbulence shall be provided if the distance between them islower than the appropriate wake turbulence minimum.

Instrument approach

The approach controller shall specify the instrument approach procedure to be used by the arriving aircraft. A flight crew may request an alternative approach procedure and, if circumstances permit, should be cleared accordingly.

If visual reference is established before completion of the approach procedure, the entire procedure must be executed unless the aircraft requests and is cleared for a visual approach.

Holding

In the event of extended delays, aircraft should be advised of such delay, and be permitted to reduce speed in order to absorb some of the arrival delay.

When delay is expected the area control center shall normally be responsible for clearing aircraft to the holding fix and for including holding instructions, expected approach time or onward clearance time as applicable.

Operations on parallel runways

Departing aircraft

Types of operation

Parallel runways may be used for independent instrument departures in the following modes:

- Both runways used exclusively for departures (independent departures); or

- One runway is used exclusively for departures while the other is used for a mixture of departures and arrivals (semi-mixed operations); or

- Both runways are used for mixed arrivals and departures (mixed operations)

Requirements and procedures for independent parallel departures

Independent parallel IFR departures may be conducted on parallel runways provided:

- The minimum distance between runway centerlines is at least 760 m; and

- Departure tracks diverge by at least 15 degrees immediately after take-off; and

- A suitable surveillance system capable of identifying aircraft within 1 NM of the runway is available; and

- ATS operational procedures ensure that track separation is achieved.

Arriving aircraft

Types of operation

Parallel runways may be used for simultaneous instrument operations for:

- Independent parallel approaches; or

- Dependent parallel approaches; or

- Segregated parallel approaches

Requirements and procedures for independent parallel approaches

Independent parallel approaches may be conducted provided that:

- The minimum distance between runway centerlines is 1035 meters and suitable ATS surveillance equipment is available such as SSR, MLAT or ADS-B; and

- Instrument landing system (ILS) approaches are being conducted on both runways; and

- The missed approach track for one approach diverges by at least 30 degrees from the missed approach track of the adjacent approach; and

- Aircraft are advised of the runway identification as early as possible; and

- Vectoring is used to intercept the final approach course; and

- A no transgression zone (NTZ) at least 610 meters wide equidistant between runway centerlines must exist and be clearly marked on the radar display; and

- Separate controllers monitor the approaches to each runway and ensure that where 1000 ft vertical separation is reduced, aircraft do not enter the NTZ and applicable longitudinal separation between aircraft on the same localizer course is maintained; and

- Transfer of control is initiated before the higher of the two aircraft has intercepted the glide slope.

- The approach controller has frequency override capability over aerodrome control

As early as possible when aircraft have established communications with the approach controller, aircraft must be informed that independent parallel approaches are in use. This may be done through an ATIS broadcast.

When vectoring to intercept the ILS localizer course, the final vector should allow the aircraft to intercept at an angle of not greater than 30 degrees and allow for at least 1.0 NM of straight and level flight before the localizer intercept. The vector should also enable the aircraft to fly straight and level for at least 2.0 NM after establishing on the localizer before establishing on the glide path.

A minimum of 1000 ft vertical separation or a minimum radar separation of 3.0 NM must be applied between aircraft on parallel approaches until they are established on the final approach course.

For aircraft on the same localizer course, a minimum separation of 3.0 NM shall be applied unless greater longitudinal separation is required for wake turbulence or other reasons.

When assigning the final heading to intercept the ILS localizer course, the runway shall be confirmed and the aircraft shall be advised of:

- Its position relative to a fix on the ILS localizer course; and

- The altitude to be maintained when established on the ILS localizer course until the glide slope intercept point is reached; and

- If required, clearance for the appropriate ILS approach.

When aircraft are observed to overshoot the turn-on or continue on a track that will penetrate the NTZ, aircraft shall be instructed to return immediately to the correct track.

When an aircraft is observed entering the NTZ, the aircraft on the adjacent ILS localizer course shall be immediately instructed to climb and turn to the assigned heading/altitude to avoid the deviating aircraft.

Flight path monitoring shall not be terminated until:

- Visual separation is applied, provided both controllers are advised wherever visual separation is applied;

- The aircraft has landed, or in the case of a missed approach, 1.0 NM from the departure end of the threshold.

Suspension of independent parallel approaches

Independent parallel approaches shall be suspended to runways with centerlines that are spaced less than 1525 meters from each other under certain meteorological conditions such as wind shear, turbulence, crosswind, and thunderstorms, which may increase the instances of localizer deviations.

Requirements and procedures for dependent parallel approaches

Dependent parallel approaches may be conducted provided:

- The runway centerlines are spaced by 915 meters; and

- Aircraft are vectored to intercept the final approach track; and

- Suitable SSR equipment is available; and

- ILS approaches are conducted on both runways; and

- Aircraft are advised that approaches are in use for both runways (this may be provided in the ATIS); and

- The missed approach track for one approach diverges by 30 degrees from the missed approach track of the adjacent approach; and

- Approach control has frequency override capability over aerodrome control.

A minimum vertical separation of 1000 ft or a minimum radar separation of 3.0 NM is is provided to aircraft during the turn-on to intercept the localizer course.

The minimum radar separation between aircraft established on the final approach course shall be:

- 3.0 NM for aircraft on the same localizer course unless increased longitudinal separation is required for wake turbulence; or

- 2.0 NM between aircraft established on adjacent localizer courses

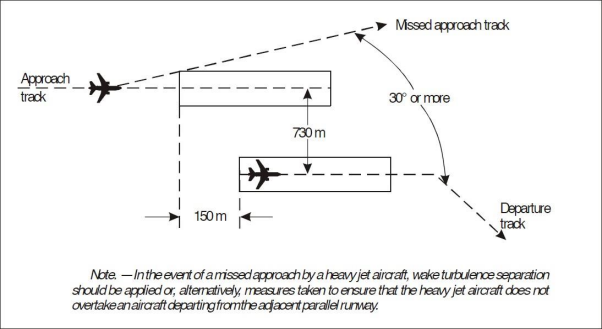

Requirements and procedures for segregated parallel operations

Segregated parallel operations (Figure 4-1) may be conducted on parallel runways:

-

The runway centerlines are spaced by 760 meters

-

The nominal departure track diverges by at least 30 degrees from the missed approach track of the parallel approach.

The minimum distance between parallel runway center lines for segregated parallel operations may be decreased by 30 meters for each 150 meters the arrival runway is staggered toward the arriving aircraft, to a minimum of 300 meters (Figure 4-2).

The following types of approaches may be conducted in segregated parallel operations provided suitable surveillance radar and suitable ground services are available such as an ILS.

ATS Surveillance Services

General Procedures

Aircraft identification

For aircraft to be provided ATS surveillance services, aircraft identification must be established, and the pilot informed. Identification should then be maintained until the termination of ATS surveillance.

Identification on a secondary surveillance radar system (SSR) is established by one of the following methods:

- Recognition of the setting of a discrete transponder code (i.e., not ending in 00)

- Observation of the IDENT feature of an aircraft transponder where a discrete transponder code has already been assigned.

Once radar identification has been established the pilot shall be informed. If at any time identification is lost or ATS surveillance service terminated, this pilot shall also be informed.

Position information

Where identification has been performed the aircraft should be informed of its position except in the following cases:

- Transfer of identification from one controller to another; or

- Assigned discrete SSR code identification and the aircraft’s position is consistent with its expected position based on its flight plan; or

- Based on the pilot’s report of position or within 1 NM of the departure runway and consistent with the planned departure time of the aircraft.

Position information shall be passed in the following forms:

- As a well-known geographical location; or

- As a magnetic track and distance from a significant point, enroute navigational aid or approach aid; or

- Direction (using points of a compass) from a known position; or

- Distance to touchdown if the aircraft is on final approach; or

- Distance and direction from the centerline of an ATS route.

Wherever practical, position information shall be made with reference to positions or routes relevant to the aircraft concerned.

Radar vectoring

Vectoring is achieved by assigning aircraft specific headings which will enable the aircraft to maintain the desired track.

When vectoring an aircraft, controllers should comply with the following:

- When an aircraft is given its initial vector diverting it from a previously assigned route, the pilot shall be informed of what the vector is to accomplish, and the limit of the vector should be specified (e.g., to position for approach).

- Controlled flights shall not be vectored into uncontrolled airspace except in case of emergency or to avoid adverse meteorological conditions, or on the specific request of the pilot.

When vectoring an IFR flight and when giving an IFR flight a direct routing which takes the aircraft off an ATS route, the controller should ensure that the minimum obstacle clearance exists at all times until the aircraft reaches a point where it is able to resume its own navigation.

When radar vectors are terminated, the controller shall issue an appropriate instruction to the aircraft to return it to its pre-planned route, and the aircraft should be instructed to resume own navigation.

Application of separation

Separation shall only be applied with reference to ATS surveillance systems if there is reasonable assurance that identification of aircraft will be obtained and maintained.

When the control of an identified aircraft will be transferred to a sector that applies procedural separation, or a higher separation minima, this separation must be applied before the aircraft enters the next sector, or the sector of airspace where the higher separation minima applies.

Under no circumstances should the symbols on the radar screen touch or overlap unless vertical separation is assured.

Separation minima based on ATS surveillance

SSR/ADS-B/MLAT based separation minima

When aircraft are under ATS surveillance either from SSR, ADS-B or MLAT, the minimum horizontal separation is 5.0 NM.

This may be reduced to 3.0 NM when radar and/or ADS-B and MLAT systems capabilities at a given

location permit.

Separation minima on final approach

A minimum separation of 2.5 NM may be applied between aircraft under ATS surveillance when established on the final approach course within 10 NM of the runway threshold provided:

- The average runway occupancy of aircraft is not more than 50 seconds; and

- Braking action is reported as good and runway occupancy times are not adversely affected by contaminants such as slush, ice, and snow; and

- The aerodrome controller is able to observe visually or by means of surface movement radar or surface movement guidance and control (SMGCS), the runway in use and exit and entry taxiways; and

- Distance based wake turbulence minima do not apply; and

- Aircraft approach speeds are closely monitored by the controller and adjusted where necessary to ensure minimum separation; and

- Aircraft operators and pilots have been made fully aware of the need to exit the runway in an expeditious manner at the assigned exit taxiway

Separation from adjacent airspace

Except where transfer of control to be made, aircraft shall not be vectored closer than 2.5 NM to the boundary of the airspace that a controller is responsible for unless there has been prior coordination with the controller of the adjacent sector. This ensures that minimum horizontal separation will always exist between aircraft in different sectors.

Distance-based wake turbulence separation minima

The following distance-based wake turbulence separation minima shall by applied (Table 5-1) when aircraft are under ATS surveillance during the approach and departure phases of flight.

These minima shall be applied under the following circumstances:

- An aircraft is operating directly behind another at the same altitude or less than 1000 ft below; or

- Both aircraft are using the same runway, or a parallel runway separated by less than 760 meters; or

- An aircraft is crossing behind another aircraft at the same altitude or less than 1000 ft below

| Preceding Aircraft Category Succeeding Aircraft Category Separation Minima | Succeeding Aircraft Category | Separation Minima |

|---|---|---|

| SUPER | HEAVY | 6 NM |

| MEDIUM | 7 NM | |

| LIGHT | 8 NM | |

| HEAVY | HEAVY | 4 NM |

| MEDIUM | 5 NM | |

| LIGHT | 6 NM | |

| MEDIUM | LIGHT | 5 NM |

Table 5-1: Distance-based wake turbulence separation minima

Separation from aircraft that are holding

Where vertical separation does not exist between aircraft established in a holding pattern and aircraft not holding, a minimum of 5.0 NM of horizontal separation must exist.

Separation of aircraft on reciprocal tracks

Where confirmation has been obtained from radar derived that aircraft on reciprocal tracks have passed, there is no requirement to ensure that minimum radar separation exists before reducing the minimum vertical separation provided:

- Both aircraft are properly identified; and

- Radar label leader lines for both tracks are not crossed; and

- The distance between the position symbols is increasing; and

- The position symbols are not touching or overlapping

Verification of Mode C altitude readout

Verification of pressure-altitude-derived level information Mode C displayed to the controller shall be affected by simultaneous comparison (reported and observed at least once on initial contact by the first controller providing a surveillance service), when an aircraft enters civil controlled airspace after departure from an aerodrome.

Following successful verification, the Mode C information may be considered to remain verified provided it is associated with a Mode A SSR Code that has been previously validated by another controller and that the observed Mode C information has an error of 200ft or less at all levels.

Determination of level occupancy

Maintaining a level

An aircraft may be considered to be maintaining a level when the observed altitude readout is within the tolerances, of the assigned level, as laid down in 5.4.8.

Vacating a level

An aircraft can be considered to have vacated a level during a climb or descent when the observed altitude readout is more than 200ft from the previously occupied level, in the anticipated direction.

Passing a level

An aircraft may be considered to have crossed a level during a climb or descent when the observed altitude readout has passed the level by more than 200ft in the required direction.

Reaching a level

An aircraft may be considered to have reached a level to which it had been cleared when whichever is the greater of 3 sensor or display updates, or 15 seconds has passed since the level information has indicated that it is within the appropriate tolerance required in 5.4.8.

Departing a runway

Aircraft may be considered to have departed a runway when the surveillance display indicates a positive rate of climb from the aerodrome elevation. However, Mode C information shall not be used

when the display varies by more than 200ft from the aerodrome elevation during the take-off roll.

Aerodrome Control Service

General provisions

Aerodrome control towers issue information and clearances to aircraft under their control to achieve a safe, orderly, and expeditious flow of air traffic at and in the vicinity of an aerodrome. The main objective of aerodrome controllers is to prevent collisions between:

- Aircraft flying within the designated area of responsibility of the control tower, including the aerodrome traffic circuit;

- Aircraft operating on the maneuvering area;

- Aircraft landing and taking off;

- Aircraft and vehicles operating on the maneuvering area;

- Aircraft of the maneuvering area obstructions on that area;

Aerodrome controllers should maintain a continuous watch on all flight operations on and in the vicinity of the aerodrome. Watch shall be maintained by visual means which may be augmented by ATS surveillance under low visibility conditions.

The function of an aerodrome controller is normally performed by different positions:

- Aerodrome controller, responsible for operations on the runway and aircraft flying within the area of responsibility of the control tower (control zone);

- Ground controller, responsible for traffic on the maneuvering area with the exception of runways;

- Clearance delivery position, normally responsible for the delivery of IFR clearances and, where necessary the adjustment of start-up times.

Where parallel or near-parallel runways are used for simultaneous operations, individual aerodrome controllers should be responsible for operations on each of the runways.

Control of aerodrome traffic

Designated positions of aircraft in the aerodrome traffic and taxi circuits

The following positions in the aerodrome traffic and taxi circuits are where aircraft receive clearance from the aerodrome control tower (Figure 6-1). Aircraft should be watched closely as they approach these positions so that proper clearances may be issues without delay. Wherever possible, the controller should initiate the radio call without having to be contacted by the pilot.

- Aircraft initiates call to taxi for departing flight. Runway-in-use information and taxi clearances given (runway-in-use may be omitted if the aerodrome has a functional ATIS).

- If there is conflicting traffic, the departing traffic will be held at this position. Engine run-up will, when required, normally be performed here.

- Take-off clearance is issued here, if not practicable at position 2.

- Clearance to land is issued here as practicable.

- Clearance to taxi to apron is issued here.

- Parking information is issued here, if necessary.

Control of taxiing aircraft

Prior to issuing taxi clearance, controllers should establish where on the aerodrome and aircraft is parked. Taxi clearances should be concise and provide adequate information so that pilots are able to follow the correct taxi route, avoid a collision with other aircraft, and minimize the occurrence of aircraft inadvertently entering an active runway.

When a taxi clearance contains a clearance limit beyond that of an active runway, explicit instruction must be given to aircraft to hold short of or cross that runway.

A taxi route should wherever possible be described by the use of taxiway designators, runway designators. Wherever required, instructions to follow or give way to other taxiing aircraft should be provided.

Aircraft shall not be permitted to line up or hold on the approach end of a runway-in-use whenever another aircraft is landing, until the landing aircraft has passed in front of the aircraft holding short.

Control of traffic in the aerodrome traffic circuit

Aircraft in the traffic circuit shall be separated in accordance with the minima listed in 6.3 except:

- Aircraft operating in different areas or different runways on aerodromes suitable for simultaneous runway operations.

- Military aircraft

Sufficient separation should be maintained for aircraft operating in the traffic circuit to allow for arriving or departing aircraft.

Aircraft should be cleared to join the traffic circuit in a direction which conforms with other aircraft already in the circuit. In addition, an aircraft may be instructed to join any part of a traffic circuit.

IFR aircraft executing an instrument approach should be allowed to make a straight in approach unless visual maneuvering is required for the completion of the procedure (such as a circling approach).

Order of priority for arriving and departing aircraft

An aircraft in the final stages of an approach to a runway shall be given priority over aircraft intending to depart from the same or intersecting runway.

Runway incursion or obstructed runway

If an aerodrome controller, after a take-off clearance or a landing clearance has been issued becomes aware of a runway incursion, or imminent runway incursion, the following action should be taken:

- Cancel the take-off clearance for a departing aircraft;

- Instruct a landing aircraft to execute a go-around or missed approach;

- In all cases inform the aircraft of the obstruction or incursion and its location in relation to the runway.

Control of departing aircraft

Departure sequence

Departures should normally be cleared for take-off in the order which they are ready, except where deviations may be made in this order of priority to facilitate the maximum number of departures with the least average delay.

Factors which should be taken into consideration are:

- Types of aircraft and their relative performance;

- Routes to be followed take-off

- Any specified minimum departure interval between take-offs;

- Need to apply wake turbulence separation minima;

- Aircraft which should be afforded priority;

- Aircraft subject to ATFM requirements.

Separation minima

Except where wake turbulence separation (6.6), departure track separation (6.7) or reduced minima (6.5) is applied, aircraft will normally only be cleared for take-off:

- Once the preceding aircraft has crossed the end of the runway in use; or

- The preceding departing aircraft has commenced a turn to clear the runway; or

- Until all preceding landing aircraft are clear of the runway in use

(See figure 6-2)

Take-off clearance

Take-off clearance may be issued when there is reasonable assurance that the separation minima in 6.3.2 or 6.5 will exist when the aircraft commences take-off.

The expression “TAKE-OFF” shall only be used when issuing or cancelling a take-off clearance.

Subject to 6.3.1, take-off clearance shall be issued when the aircraft is ready for take-off at or approaching the runway holding point. To minimize confusion, the runway designator should be included in the take-off clearance.

In the interest of expediting traffic, a clearance for immediate take-off may be issued to an aircraft before it enters the runway. The aircraft will be expected to carry out the lineup and take-off in one continuous movement.

Control of arriving aircraft

Separation minima

Except where wake turbulence separation (6.6), departure track separation (6.7) or reduced minima (6.5) is applied, aircraft will only be cleared to cross the landing threshold when:

- The preceding departing aircraft has crossed the end of the runway-in-use or has started a turn; or

- The preceding landing aircraft is clear of the runway-in-use. (See Figure 6-2)

Landing clearance

Landing clearance may be issued when there is reasonable assurance that the separation minima in 6.4.1 and 6.5 will exist when the aircraft crosses the runway threshold, provided that a clearance to land will not be provided until a preceding landing aircraft has crossed the runway threshold. To reduce the potential for misunderstanding, the runway designator shall be included in the landing clearance.

Landing roll-out maneuvers

Where necessary to expedite traffic, a landing aircraft may be instructed to vacate at a specified exit point, or to expedite vacating the runway.

In requesting aircraft to perform specific landing roll-out maneuvers, the type of aircraft, location of exit, runway length, meteorological conditions and reported braking action should be considered by the controller.

When necessary or desirable (such as during low visibility operations) an aircraft may be instructed to report when a runway has been vacated.

Reduced runway separation minima (RRSM)

Subject to a safety assessment for specific aerodromes, lower separation minima than those specified in 6.3 and 6.4 may be used and is termed as reduced runway separation minima (RRSM).

RRSM must not be applied between a departing aircraft that is following a preceding landing aircraft.

RRSM is subject to the following conditions:

- Wake turbulence separation minima shall be applied;

- Visibility shall be at least 5 km and ceiling not less than 300 ft;

- Tailwind component should not exceed 5 kt;

- There shall be available means such as suitable landmarks that allow controllers to assess the separation between aircraft. A surface surveillance system may be utilized to fulfil this requirement;

- Minimum separation continues to exist between two departing aircraft immediately after the take-off of the second aircraft;

- Traffic information shall be provided to the crew of the succeeding aircraft;

- Braking action shall not be adversely affected by contaminants such as slush, ice or snow.

Time-based wake turbulence separation minima (non-radar)

Applicability

Wherever applicable, controllers shall be responsible for the application of the wake turbulence separation minima specified in 5.4.4.

ATC shall not be required to apply wake turbulence separation for the following cases:

- Arriving VFR flights landing on the same runway as a preceding SUPER, HEAVY or MEDIUM aircraft; and

- Between IFR flights executing a visual approach when the aircraft has reported the preceding aircraft in sight and has been instructed to follow and maintain own separation

Where aircraft have been instructed to maintain their own separation and where otherwise deemed necessary, ATC shall provide a caution of possible wake turbulence. It is the pilot’s responsibility in this mcase to maintain a safe following distance from the preceding arrival.

Successive departing aircraft

A minimum separation of 3 minutes shall be provided between a LIGHT or MEDIUM aircraft taking off behind a SUPER aircraft and; 2 minutes shall be applied between a HEAVY taking off behind a SUPER aircraft, and a LIGHT or MEDIUM aircraft taking of behind a HEAVY aircraft when they are using:

- The same runway

- Parallel runways separated by less than 760 meters

- Parallel runways separated by more than 760 meters if the projected flight path of the second aircraft will cross the projected flight path of the first aircraft at the same altitude or up to 1000 ft below.

A minimum separation of 4 minutes shall be applied between a LIGHT or MEDIUM aircraft taking off behind a SUPER aircraft and; 3 minutes shall be applied between a LIGHT or MEDIUM aircraft taking off behind a HEAVY aircraft and a LIGHT aircraft taking off behind a MEDIUM aircraft from:

- An intermediate part of the same runway

- An intermediate part of a parallel runway separated by less than 760 meters

Displaced landing threshold

A minimum separation of 3 minutes shall be applied between a LIGHT or MEDIUM aircraft and a SUPER aircraft and; 2 minutes shall be applied between a LIGHT or MEDIUM aircraft and a HEAVY aircraft and between a LIGHT aircraft and a MEDIUM aircraft when operating on a runway with a displaced landing

threshold when:

- A departing LIGHT or MEDIUM aircraft follows a SUPER aircraft arrival and a departing LIGHTaircraft follows a MEDIUM aircraft arrival; or

- An arriving LIGHT or MEDIUM aircraft follows a HEAVY or SUPER aircraft departure and an arriving LIGHT aircraft follows a MEDIUM aircraft departure if the projected flight paths areexpected to cross.

Separation of successive IFR departures

Departures on diverging tracks

For successive IFR departures, if the departure track of a following aircraft diverges by more than 30 degrees from the leading aircraft, and the controller has confirmed by visual observation, the following aircraft may be cleared for take-off when:

- The leading aircraft has reached a point where appropriate separation will exist from the following aircraft; or

- The leading aircraft has turned to clear the departure track of the following aircraft

If the departure track of a following aircraft differs by more than 20 degrees from the leading aircraft, the following aircraft may be cleared for take-off when:

- Radar identification will be established within 1 NM of the departure end of the runway used for take-off; and

- The leading aircraft is more than 1 NM ahead of the following aircraft and confirmed by visual or radar observation as having turned to clear the departure track of the following aircraft.

Departures on the same track

The separation between two successive IFR departures following the same departure track is 2 minutes, provided the leading aircraft maintains a speed 40 knots or more higher than the trailing aircraft (Figure 6-5).

Horizontal Speed Control

General

Speed control is one of the most desirable ways to achieve or maintain a desired separation between aircraft. In general, it results in the smallest increase in controller workload and is particularly useful when sequencing aircraft (such as towards a TMA entry point).

The primary variable affecting the future position, and consequently, separation between aircraft is ground speed. However, it is generally impractical to instruct aircraft to maintain a certain ground speed. Therefore, speed assignments are made with reference to indicated airspeed (IAS) or Mach number.

Use of horizontal speed control

Speeds may be used to:

- Adjust separation (different speeds applied between aircraft)

- Maintain separation (the same speed applied between aircraft)

- Absorb delay by reducing speed enroute (as an alternative to holding)

- Avoid or reduce vectoring:

- As an alternative to vectoring

- In combination with vectoring to reduce the number and magnitude of heading changes required

Considerations

Applying speed control

Most jet turbine aircraft will be unable to quickly increase or decrease speed, especially at higher altitude, so due consideration must be given to the time taken for an aircraft to reach a desired speed. In certain cases, the speed control may need to be applied, one or two miles prior to when the desired spacing is achieved.

Due consideration must also be given to prevailing winds aloft, as a headwind will decrease an aircraft’s ground speed and a tailwind will increase an aircraft’s ground speed. This may affect the magnitude of the speed instruction that is given to an aircraft.

Aircraft performance characteristics

Speeds in excess of the maximum or minimum speeds shall not be assigned to aircraft. Due consideration must be given to the performance characteristics of different aircraft. This ensures that aircraft do not operate too close to high speed/low-speed buffet regions of the flight envelope, especially for aircraft at higher levels (FL350 and above). (See Table 7-1)

| Aircraft category | Safe operating Mach | Maximum IAS (below FL250) |

|---|---|---|

| SUPER (A380) | 0.82 – 0.87 | 330 |

| HEAVY (B747, B787, A350) | 0.82 – 0.87 | 330 |

| HEAVY (B777, B767, A330, MD11) | 0.81 – 0.85 | 320 |

| MEDIUM (A320, B737) | 0.75 – 0.79 | 300 |

Table 2-1: Safe operating speed and Mach number ranges

Speed control during climb or descent

Instructions for aircraft to maintain a high rate of descent and a low speed, or a high rate of climb and high speed, are generally incompatible.

When aircraft are instructed to increase speed during a climb or decrease speed during a descent, they can be expected to maintain a short period of level or near-level flight in order to comply with the speed instruction. Conversely, when aircraft are instructed to reduce speed during a climb or increase speed during a descent, they can be expected to increase their rate of climb or descent, respectively.

Effectiveness

Speed control generally takes more time to achieve the desired separation as compared to other techniques such as vectoring, so due consideration must also be given to the volume of airspace available to achieve the desired separation.

The longer the controller waits before applying speed control, the more drastic the speed change needs to be in order to achieve the desired separation at the handover point. Should this be the case, the controller should revert to vectoring to achieve separation.

Relationship between Mach number and true airspeed

When aircraft are flown with reference to Mach number, the true airspeed of an aircraft will decrease with increasing altitude. This must be considered when applying Mach number control between aircraft at different flight levels, as aircraft at higher levels will be flying slower than those at lower levels despite reporting the same Mach number.

Relationship between indicated airspeed and true airspeed

When aircraft are being flown with reference to indicated airspeed, their true airspeed will increase with increasing altitude. Therefore, aircraft at higher altitude will be flying faster than those at lower altitude, despite reporting the same indicated airspeed.

Mach/airspeed crossover

Aircraft climbing under speed control should be given a Mach number to maintain during the crossover point between indicated airspeed and Mach number to ensure that they maintain a safe operating margin and do not unexpectedly increase speed during the climb.

Conversely, descending aircraft should be given an indicated airspeed to maintain during the crossover, so their speed does not continue to increase as the aircraft descends.

Rules of thumb

- 0.01 Mach = 6 knots

- Speed difference of 6 knots gives 1 NM of separation change every 10 minutes

- Speed difference of 30 knots gives 1 NM of separation change every 2 minutes

- Speed difference of 60 knots gives 1 NM of separation change every minute

- True airspeed (TAS) = Indicated airspeed (IAS) + 6 knots per 1000 ft above MSL

Vectoring

General

Vectoring is achieved by instructing aircraft to maintain a heading that will result in it following a desired ground track. It is one of the most effective techniques to establish and maintain horizontal separation between traffic and is far more effective than speed control in doing so, producing the desired result much more quickly. However, it results in a larger increase in controller as compared to other methods.

When aircraft are placed on a vector, they must be informed of the reason for the vector, and the expected point where they are expected to re-join the flight planned route.

The procedures laid down in 5.2 shall apply when aircraft are under radar vectors.

Use of vectoring

Navigation assistance

Should aircraft navigational equipment fail, or ground navigational aids are unavailable, vectoring may be used to provide navigational assistance to aircraft.

This may also be used to provide navigational assistance to VFR aircraft should they become lost.

Circumnavigating airspace

If aircraft is approaching special use airspace such as danger, restricted and prohibited areas and a climb or descent is unfeasible, aircraft may be vectored around the airspace.

Conflict prevention

In situations where there is adequate separation between aircraft projected to cross each other at the same level, but it is only slightly above separation minima, aircraft may be instructed to “MAINTAIN PRESENT HEADING”.

This technique of “locking” the heading ensures that the minimum separation will be maintained between aircraft, and the aircraft will not make any turns such as to follow an airway or terminal procedure.

Conflict solving

If a level change is not possible, or practical, aircraft may be issued a heading change in order to ensure horizontal separation minima is maintained. In most cases, only a relatively small change in heading is required to achieve the desired result. This results in a minimal change to the aircraft’s total flight distance and therefore to its fuel consumption.

After the conflict has been solved and separation is assured aircraft may be instructed to resume their own navigation.

Sequencing

Aircraft may be sequenced to a sector boundary point using a combination of speeds and vectors. The objective of sequencing is to establish and maintain a minimum separation between the leading and following aircraft.

Vectoring geometry

Conflict geometry

Crossing point

The crossing point is the point where the projected flight paths between two aircraft are expected to cross. It is fairly easy to determine the crossing point as it is only dependent on the projected tracks of two aircraft and is unaffected by speed and wind.

Closest point of approach (CPA)

The minimum distance between two aircraft at the time they pass each other is known as the closest point of approach (CPA). In general, the separation between two aircraft continues to reduce after the first aircraft crosses the track of the second aircraft until reaching the CPA.

CPA is dependent on the angle of the trajectories of the two aircraft and their projected ground speed and therefore the time taken to reach the crossing point. For this reason, it is more complex to calculate than crossing point as it requires the use of trigonometry.

Closest point of approach is displayed on the radar screen along the projected path of an aircraft and is color coded yellow. A red color code indicates that the CPA is below the required separation minima. It should be noted, however that this is an instantaneous prediction and may not necessarily be accurate if aircraft vertical and horizontal speed change and should therefore be used with caution.

Determining CPA

- A crossing angle of 90 degrees means separation will be reduced by 30% between crossing point and CPA. As a result, a separation of 7.2 NM at the crossing point is required to ensure 5 NM separation at CPA.

- A crossing angle of 60 degrees means separation will be reduced by 20% between crossing point and CPA. As a result, a separation of 6.3 NM at the crossing point is required to ensure 5 NM separation at the CPA.

- A crossing angle of 60 degrees means separation will be reduced by 10% between crossing point and CPA. As a result, a separation of 5.6 NM is required at the crossing point to ensure 5 NM separation at the CPA.

- A crossing angle of 120 degrees means separation will be reduced by 50% between the crossing point and the CPA. As a result, a separation of 10 NM is required at the crossing point to ensure 5 NM separation at the CPA.

- A crossing angle of 150 degrees means separation will be reduced by 75% between the crossing point and CPA. As a result, a separation of 20 NM is required at the crossing point to ensure 5 NM separation at the CPA.

Selecting the aircraft

Vectoring both aircraft

This is the most commonly used method to solve conflicts on reciprocal tracks. Although it increases controller workload, as multiple transmissions need to be made to different aircraft, it has less of an impact on each aircraft’s trajectory resulting in a minimal increase in distance flown. For this technique to work, both aircraft need to alter course in the same direction (e.g., both turn mright).

Vectoring the aircraft behind

This method is used when two aircraft are maintaining altitude and one is overtaking the other. The aircraft further from the crossing point is given a vector to increase separation. This is much more effective than vectoring the aircraft closer to the crossing point.

Vectoring the aircraft requesting a level change

If accommodating a climb or descent request would cause and aircraft to pass through the level of another and subsequently result in insufficient separation between them, the aircraft requesting the level change is usually the one that is given the vector.

This is usually done in three steps, first a vector is given to establish lateral separation between the two aircraft, followed by a vector to parallel the track, while at the same time accommodating the climb request. Once the aircraft has passed through the level of the other with sufficient vertical separation, a direct routing is given to the requesting aircraft to re-establish it on the planned track.

More complex situations

In more complex situations where the aforementioned techniques would not necessarily, generally controllers should follow the principle of requiring minimal intervention to achieve the desired result.

Turn direction

Aircraft on reciprocal tracks

Aircraft on opposing tracks should be vectored in the direction that would increase separation

Aircraft on crossing tracks

The aircraft further away from the crossing point should be “aimed” at the current position of the aircraft closer to the crossing point. This results in the distance from the crossing point of the leading aircraft to be reduced significantly, where the distance from the crossing point of the second aircraft is only marginally reduced. This method causes the second aircraft to pass behind the first.

For example, if the aircraft further from the crossing point has traffic on the left-hand side, it should be turned to the left to “aim” it towards the crossing traffic. Although it may seem counter-intuitive, this method will increase the separation between the aircraft.

Aircraft on the same track requesting a level change

The requesting aircraft should be turned into the wind, which will result in a reduction in its ground speed, resulting in a larger rate of increase of separation and placing the aircraft being vectored further behind. A sufficiently strong wind can be much more effective than speed control in managing an aircraft’s speed.

Consideration of the planned track

When aircraft are being vectored, due consideration must also be given to the planned flight paths of the aircraft such that the vector does not result in a significant increase in the track miles flown by the aircraft. In this case, aircraft may be issued a direct routing to “cut the corner”, which will have the same effect as a vector in that direction.

Airspace consideration

The dimensions of the airspace must also be considered when issuing vectors to aircraft. Aircraft shall not be vectored closer than 2.5 NM to the boundary of the airspace that a controller is responsible for, as this may require other actions such as coordination and further conflict solving.

Crossing angle

After the direction of turn is selected, the extent of the heading change must be determined. The crossing angle is crucial as it determines:

- The increase of separation after vectoring

- The separation reduction between the crossing point and the CPA The general impact of the crossing angle is as follows:

- Right angle (crossing) tracks allows the 1-in-60 rule to be used

- Acute angle (similar) tracks lead to:

- Less separation gained be vectoring as opposed to other options. This scenario may sometimes require a heading change of 20 degrees or more, and if wind conditions are unfavorable, it may require an even greater turn.

- In combination with vectoring to reduce the number and magnitude of heading changes required

- Obtuse angle (reciprocal) tracks lead to:

- Greater separation reduction after the crossing point

- More separation gained by vectoring. A small turn of 5 to 10 degrees is often enough to achieve the desired separation.

Associated risks

Forgetting that an aircraft has been issued a vector

This has a negative impact on flight efficiency and may also “surprise” the next controller if the airway or arrival procedure makes a sharp turn at the transfer point and the aircraft does not.

To mitigate this risk, the aircraft tag is marked before handoff to the next controller when the aircraft is placed under radar vectors.

Miscalculation of wind impact

If a controller attempts to sequence an aircraft behind another and by turning but instructs the aircraft to turn so the tailwind increases, the maneuver may have no effect as the tailwinds increases the aircraft’s speed effectively reducing the expected benefit from vectoring.

In addition, the wind speed and direction may be different at different levels and may vary significantly. Consequently, the headwind/tailwind/crosswind component will also vary, affecting the desired result. For example, the drift angle may be different at different levels, resulting in aircraft flying on converging tracks despite flying parallel headings.

This may be mitigated by assigning slightly diverging headings to aircraft being vectored.

Miscalculation of aircraft performance

Generally climbing aircraft increase their ground speed and descending aircraft will reduce their ground speed. The speed at cruise level may be up to twice as high as the speed at lower altitudes.

To mitigate this risk, controllers must always have an awareness of the performance characteristics that are altered by changes in altitude.

Rules of thumb

- Turn radius in NM = Ground speed in knots / 100

Level Change

General

During various phases of flight, level changes by aircraft may be necessary for the purpose of separation.

When issuing a level change clearance, vertical and horizontal separation between aircraft shall always be assured. Controllers must ensure that the cleared level will not result in a loss of separation with any other traffic in the vicinity prior to issuing a level clearance.

Due consideration be given to aircraft on crossing or reciprocal tracks, as well as aircraft that are on the same track which may be separated vertically but may not have adequate horizontal separation.

If there is any doubt as to whether separation will be assured an alternative clearance must be provided.

Level change clearance

Climb clearance

During a climb, when an aircraft is expected to cross, or is on the same track as proximate traffic and separation may reduce to below minimum horizontal separation, they shall only be cleared:

- To a level 1000 ft below traffic that is maintaining level flight; or

- To a level vacated by traffic if its mode C readout indicates a climb; or

- To a level 1000 ft below the clearance level of traffic that is descending

Descent clearance

During a descent, when an aircraft is expected to cross, or is on the same track as proximate traffic and separation may reduce to below minimum horizontal separation, they shall only be cleared:

- To a level 1000 ft above traffic that is maintaining level flight; or

- To a level vacated by traffic if its mode C readout indicates a descent; or

- To a level 1000 ft above the clearance level of traffic that is climbing

Horizontal speed control in combination with a level clearance

For two or more aircraft on the same track, the level clearance requirements in 9.2.2, and 9.2.3 may be exempted provided horizontal speed control has been applied and appropriate minimum horizontal separation exists and will continue to exist.

Vertical speed control in combination with a level clearance

For aircraft on crossing tracks, the requirements in 9.2.2 and 9.2.3 may be exempted, provided adequate vertical speed control has been applied and adequate horizontal separation exists and will continue to exist throughout the level change maneuver.

Associated risks

Incorrect altimeter setting

An incorrect altimeter setting between QNH and standard pressure may result in a loss of separation between aircraft at transition level and transition altitude. To mitigate this risk, an additional buffer shall be used between transition altitude and level.

Confusion between altitude and flight level

Often, confusion may occur between the terms “ALTITUDE” and “FLIGHT LEVEL”. In order to mitigate this risk, controllers must be vigilant when listening to a read back of the cleared level when transitioning between altimeter settings and reiterate the clearance and pass the QNH if necessary.

Level busts

Aircraft maintaining a very high rate of climb or descent may overshoot the cleared level in some circumstances. If aircraft are expected to maintain a high rate or climb descent, an additional buffer of vertical separation may be required in order to ensure that a level bust will not result in a loss of mseparation.

Rules of thumb

- Aircraft will lose approximately 300 ft per 1 NM travelled forward during descent

- Aircraft need 10 NM to lose 3000 ft

- Aircraft need 16 NM to lose 5000 ft

- Aircraft need 33 NM to lose 10,000 ft

- A tailwind will increase descent track miles required; a headwind will decrease descent track miles required.

- If a rapid descent is required, aircraft should be instructed to maintain a high airspeed and

then reduce speed during level flight.

Vertical Speed Control

General

Vertical speed is a useful method of maintaining separation between aircraft that are climbing or descending. Aircraft may be instructed to maintain a specific climb or descent rate. This is most useful when aircraft are climbing or descending through the level of other aircraft or are descending in a holding pattern.

Application of vertical speed control

Vertical speed control may be applied:

- To accommodate climb requests (by requesting an aircraft to expedite passing a level)

- For separation of arriving and departing traffic in opposite directions

- To descend arriving aircraft below enroute traffic

- For vertical sequencing between climbing or descending aircraft

- For corrective action (when unrestricted vertical speed is insufficient)

Benefits

Efficiency

Effectively used vertical speed control allows for continuous climbs and descents and therefore better efficiency. In addition, it permits descents to start close to top of descent and allows timely accommodation of climb and descent requests.

Reduced controller workload

This method also ensures vertical separation is maintained, resulting in reduced workload because of a reduced need for vectoring and/or horizontal speed control.

Risks

Reduced separation

The margin for error is reduced as this method relies on maintaining minimum vertical separation, which is much lower than minimum horizontal separation, therefore any non-compliance may result in a loss of separation between aircraft.

Non-compliance or misunderstanding

A misunderstanding of the instruction may result in the desired separation not being achieved. A correct readback does not guarantee compliance.

Aircraft may be unable to maintain the assigned rate of climb or descent beyond a certain level. If this occurs, there is a possibility the flight crew may not inform the controller.

Considerations

Aircraft performance

Certain aircraft types such as the Airbus A321 and Airbus A340 are unable to maintain high rates of climb.

In addition, climb rates can be expected to decrease when aircraft are approaching their cruise level, and will therefore generally be unable to maintain rates of climb in excess of 1000 ft/min. High temperatures will further reduce this value.

High rates of descent are generally incompatible with low airspeeds. Instructions to maintain both a high descent rate and low speed should be avoided.